-

· startups

Why you should spend your 3 college summers in New York, San Francisco, and Boston.

This post was originally published on Medium in 2013.

There’s something to be said about trying different industries or roles each summer while you’re in college. There’s also something to be said for living somewhere different each time.

The college summer is a sacred time. Yes, it’s prime time for relaxation before another stressful school year, but it’s also one of the biggest opportunities you have to explore new fields and develop yourself professionally.

Boston in the summer is a special place. With thousands of college students gone, an otherwise bustling city is made calm. A town full of academics and business leaders suddenly has more time for coffee meetings and advice.

Time spent in San Francisco is the best way to learn the ins and outs of technology, despite being unreasonably cold for the entire summer. Nowhere else can you walk down the street and see the offices and founders of companies you admire.

But there’s a special place in my heart for New York City summers. The cool nights, the sound of ice cream trucks, and the blisteringly hot subway tunnels give the city its character. You won’t find the same density of students in the same diversity of fields and industries as you will in New York.

After spending my freshman summer in Boston, my sophomore summer in New York, and my junior summer in San Francisco, I have a new appreciation for each city.

Don’t stick in the same city for your summers in college—travel and try living in a new city. Half of exploring during the summer is finding what you want to do after college. The other half is finding out where you want to do it.

-

This post was originally published on Medium in 2013.

In high school I organized a large conference for 1000+ attendees. I managed a $20,000 budget and a team of ~15 other students, planning 6 months in advance for a 2 day event.

Event planning might be the closest you can get to starting a company. You have people counting on you, you have a set of constraints, and despite months or years of planning, Murphy’s Law always seems to take hold.

Remember Eyjafjallajökull? It decided to rain ash across all of Europe as a box of 1000 gift bags for our attendees was on a freighter en route to New York. Lunch was an hour late. Ice cream melted in the unseasonably warm weather. Our registration system went down when the internet connection in the venue slowed to a crawl. People were lost in the building because of poor signage.

So much for planning.

I don’t care how smart or experienced you are, how long you have to plan, or how many people you have helping you. When something goes wrong—when everything goes wrong—your success depends on how well you can adapt and fix things. You need to be more MacGyver than Nate Silver, more Jack Bauer than Sherlock.

Problem-solving is a muscle, and just like muscles in your body there are slow-twitch and fast-twitch decisions. Engineers are great at analyzing problems over long periods of time. Trying to decide what car to buy or what framework will be most efficient? We can systematically analyze the data we have to come to a best guess. But how well do you behave under pressure? Can you find a bug in under a minute when it’s preventing millions of users from logging in? How do you respond when you have 1000 people waiting for lunch and the delivery truck is stuck in traffic?

Things always go wrong. How quickly you make those snap decisions is all that matters.

-

· startups

On big decisions and the next two years.

This post was originally published on Medium in 2013.

Today I have the honor to announce a major step in my life—after several months of applications and a few weeks of heavy consideration, I’ll be taking at least 2 years off from Harvard in December to be a member of the Thiel 20 Under 20 Fellowship. The first of many thanks go to the Thiel Foundation for giving me this opportunity and giving me their stamp of approval—it’s been an amazing interview process and I couldn’t be happier to be a part of the Thiel Fellowship community.

It wasn’t an easy decision to make, but I think my situation is unique. I’ve wanted to work full-time on education for a while, and I’ve been enveloped in entrepreneurship for the past few years. My mom is a teacher and my dad is a self-employed programmer. I’ve been breathing education since I could walk and designed my first website in 4th grade. It’s about time I put those skills to good use.

After reflecting on where I’ve been and where I hope to be, it’s clear that 99% of where I am can be attributed to other people. Amazing people who took bets on me when they shouldn’t have, people who cared enough to reach out to me, people who I could call at any time for help. Tony Tjan, in his book Heart, Smarts, Guts, and Luck, helps entrepreneurs determine what their core skill set is, and by his assessment I’m overwhelmingly luck-dominant. Let me take this time, then, to thank everyone who has helped me to this point, and in doing so describe how I got here.

My mom came to this country in high school from Cyprus after having spent time in London. Her father was a farmer and construction worker and her mother worked with textiles sewing clothing. My dad studied computer science and accounting in Egypt, then spent several years as a farmhand and sous chef in Spain and France before coming to the United States. Here, he continued studying engineering and computer science, working full-time and going to school on nights and weekends. My parents met at the City University of New York and got married a few years later. They’re the hardest working people I know, and I wouldn’t be here today without the many sacrifices they made for my education.

By 1985 or so, my mom was a first-grade teacher in a New York City public school. (She still teaches in that same first-grade classroom, and has been teaching for 28 years.) Since both my parents worked full-time, I spent the first few years of my life in a crib in the back of her classroom. (I was a well-behaved baby.) I then enrolled in that same East Harlem, New York public school as a student. Through years of their hard work, long nights, and 4-hour commutes to and from Long Island into New York City, I was contacted as a fifth grader by an organization called Prep for Prep that helps minority students get accepted into private schools. After going through several steps of interviews and being accepted, I spent 14 months going to night classes studying U.S. History, Biology, Latin,and more. I wouldn’t be where I am today without Prep—thanks to Charles Guerrero, Katy Bordonaro, and the rest of the team there for all the work they do.

After what I still consider to be the hardest academic experience of my life, I was accepted to Collegiate School, a small all-boys school on the Upper West Side. I realized there that I loved my extracurriculars above all else. I organized an environmental conference for 1000+ attendees and a $15,000+ budget. Event planning is the closest job to being a CEO I know. Everything that can go wrong will go wrong, and you absolutely need to think on your feet. Collegiate gave me the freedom to explore what I was interested in—thank you to Mrs. Foley, Dr. Beall, Mr. Hill, Mr. Gordon, and the million other teachers there who were my biggest academic and professional critics. Collegiate was my launchpad to Harvard and I can’t wait to give back to it in every way I can.

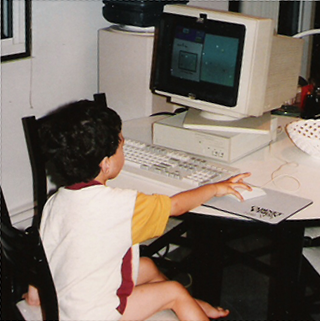

I didn’t come to Harvard as an entrepreneur, but I knew I wanted to study computer science. This was the first computer I ever used:

My dad wrote a game that helped me learn the alphabet on that machine, and computers were always around the house since he was a programmer. I wrote my first program in Visual Basic and wrote my first HTML code back in 4th grade for my own little company, Blue Box Software (the logo was suspiciously similar to today’s Dropbox logo). I took two Harvard Summer School classes in computer science and was hooked since then.

Here at Harvard, I got involved with Hack Harvard and the Innovation Lab at just the right time. Interest in entrepreneurship was beginning to pick up, so I had the opportunity to learn from some of the best startup leaders around and help fellow students who were also interested in the tech world.

So, thank you to the Innovation Lab—Gordon, Neal, Kate—for your support and mentorship over the past few years. Thanks to Harvard for accelerating my growth and helping to introduce me to some of the brightest minds in technology. Thank you to the rest of my mentors—Hugo Van Vuuren, Nick and Tuan from Tivli, Andrew Rosenthal, Bilal and Nitesh at General Catalyst, and so many others—who have been sounding boards for all my crazy ideas and questions. Thanks to my friends and roommates—Sebastian, Matt, Will, Mike—for dealing with my late nights and craziness. Thanks to one of my best friends, Andrea Brettler, who has offered her advice and support since freshman year. Special thanks go to Peter Boyce, who has been my biggest supporter and harshest critic for the past 3 years, and Perry Hewitt, who offers the most sage advice and the wittiest jokes of anyone I know.

My work at Rough Draft Ventures over the past year has shown me how dedicated student entrepreneurs can be. After funding many of the best student ideas in Boston, it’s clear that Boston and New York are now tech hubs of their own. I grew up in New York and grew academically, professionally, and intellectually in Boston. Those cities are my roots, and I hope to be the bridge between this East Coast hub that’s rapidly growing and the storied Silicon Valley ecosystem that has so much to offer the students growing companies here in Boston. I will continue to work with Rough Draft and help students, and the fact that our partners are doing such diverse things is a testament to the types of students we’re looking to fund—people are willing to drop everything they’re doing and pursue an idea relentlessly.

I couldn’t be more excited for what the next two years hold.

Then the Popular Electronics article came out. Gates’ friend Paul Allen ran through Harvard Square with the article to wave it in front of Gates’ face and say, “Look, it’s going to happen! I told you this was going to happen! And we’re going to miss it!” Gates had to admit that his friend was right; it sure looked as though the “something” they had been looking for had found them. He immediately phoned MITS, claiming that he and his partner had a BASIC language usable on the Altair. When Ed Roberts, who had heard a lot of such promises, asked Gates when he could come to Albuquerque to demonstrate it, Gates looked at his childhood friend, took a deep breath, and said, “Oh, in two or three weeks.” Gates put down the receiver, turned to Allen and said: “I guess we should go buy a manual.” They went straight to an electronics shop and purchased Adam Osborne’s manual on the 8080.

– from Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer

By Zach Hamed on May 9, 2013.

-

· startups

This post was originally published on Medium in 2013.

As I finish this semester, I thought it might be valuable to shed some light into the unique entrepreneurship scene at Harvard. It can be clichéd, but it’s hard to deny Bill Gates’s and Mark Zuckerberg’s Harvard roots. There’s increased interest in entrepreneurship on all college campuses, but at Harvard it has accelerated especially rapidly given The Social Network and the Facebook IPO. The startup scene has grown beyond recognition in the three years I’ve been on campus—I’m a junior now—so I’ll try to objectively describe the various initiatives around campus and then offer my own thoughts.

Harvard Innovation Lab

The largest addition to Harvard’s entrepreneurship efforts this year was the new Innovation Lab (i-lab for short). The 30,000-square-foot ground floor features day-use space, reserved space for incubated teams, a classroom, conference rooms, a kitchen stocked with snacks, and a game room filled with video games.

Physically, the building is on the Harvard Business School campus. While it isn’t next to the center of campus (Harvard Yard), the vast majority of entrepreneurship events are now hosted there, so many students have been spending more time there. The i-lab has hosted a startup career fair, a Startup Weekend hackathon, and office hours with venture capitalists and entrepreneurs-in-residence.

University-Sponsored Initiatives

Considering that the i-lab hosts or runs many of these initiatives, it makes sense to describe these next. The administration recently came out strongly in support of entrepreneurship, sponsoring a President’s Challenge that awarded 10 teams $5,000 each to advance their ventures in the areas of clear air, clean water, global health, personal health, and education. A panel of professors then awarded a grand-prize winner and up to three finalists a total of $100,000 to develop their ventures during the summer. While money isn’t the only solution to encouraging entrepreneurship, the resources and backing of the University certainly go a long way to helping student-led ventures.

The Experiment Fund

Probably the second most important announcement of the past term was the launch of the Experiment Fund, a seed fund run by NEA, Accel Partners, and Polaris Ventures to help fund student ventures. While the fund was initially launched at Harvard, it is expanding to include other colleges in Cambridge. The fund has already financed a few ventures, including health incubator Rock Health and TV-over-the-Internet startup Tivli.

Hack Harvard

The newest technical addition to startup extracurriculars is Hack Harvard, an organization that brings together mostly engineering students who are working on personal projects. An emphasis is placed on cool hacks or integration of third-party APIs. In the last year, they welcomed a number of technical speakers, among them Aza Raskin of Massive Health and former creative lead of Firefox. They also welcomed the Winklevoss twins and Divya Narendra of The Social Network fame.

Hack Harvard runs an incubator program over winter break for campus startups. Students learn more about web development and design through a number of workshops led by professors and upperclassmen. They spend the rest of their time advancing their projects in anticipation of a demo day for other students, investors, and the Boston community.

Rough Draft Ventures

Just a few months ago, General Catalyst helped launch a new seed-stage fund in Boston for students working on a startup of their own. Rough Draft Ventures gives students up to $25,000 in the form of an uncapped convertible note to fund their venture. Its first investment was $20,000 in Balbus Speech, a company focused on special education and speech therapy.

Zuck returns to campus

The biggest tech celebrity to come to campus in 2012 was Mark Zuckerberg, who returned for the first time since dropping out in 2004. His homecoming was billed as a recruiting talk, and he spoke to an audience of computer science students. Overall, his visit further invigorated campus interest in computer science.

Computer Science Department

The most notable addition to the Harvard CS program was Computer Science 164: Mobile Software Engineering. The class is not only an introduction to iOS programming and jQuery Mobile, but also a great primer in industry-standard software development practices, including pair programming, code reviews, source control, unit testing, MVC frameworks, and database scaling. The class is taught by star CS professor David Malan, who also teaches the introductory CS class, CS 50. CS 50, a 10-week overview of computer science in C, HTML, CSS, Javascript, PHP, MySQL, is now the second most enrolled class at the College following Introduction to Economics, demonstrating the surging popularity of CS at Harvard.

Social Entrepreneurship

The entrepreneurship scene isn’t limited to tech startups. Students are interested in social entrepreneurship across a number of areas, including education, health, clean tech, and more. Through extracurriculars like the Social Innovation Collaborative and University initiatives like the President’s Challenge, there is an emphasis on socially-oriented ventures.

Business Plan Competition Winners

There are two main business plan competitions on campus. College students enter the i3 competition, while HBS students enter the HBS Business Plan competition. Past winners of the HBS competition include Rent The Runway, Birchbox, CloudFlare, RelayRides, and thredUP. In 2012, the winner of the business venture track was Vaxess Technologies, a company working to commercialize a technology to condense vaccines into a thin film strip that can be shipped and stored without refrigeration. Here’s a full list of the winners and runners-up.

On the college level, a total of $50,000 was awarded to six major award winners for everything from a foot shape analysis technology to an iPad point-of-sale survey platform. Here’s the full list of winners.

Harvard College Venture Partners

There is also a strong interest in venture capital on campus, the main activity for which is Harvard College Venture Partners, or HCVP. HCVP brings venture capitalists and successful entrepreneurs to campus to speak with Harvard startup founders. One of its main objectives is to facilitate cross-campus collaboration, particularly with Harvard Business School students and professors.

HBS

Harvard Business School has become notably more open to sharing its resources with the rest of the University. The i-lab is one way of connecting HBS professors with undergrads and other schools. A new class taught to undergrads this year was U.S. and the World 36: Innovation and Entrepreneurship. The class—a survey on innovation across disciplines—was taught with HBS’s signature case study method. It was primarily taught by professors Joe Lassiter and Mihir Desai and co-taught by visiting professors from other Harvard schools, including the Kennedy School of Government and Engineering School. The course culminated with students working on over 40 real-world projects at various startups and organizations.

Harvard Business School students have also increasingly turned to the College to learn about CS. Enrollment in CS50 by HBS students was sharply up this past fall. Many students were happy with their decision to take it, and the increased interaction with undergrads was largely welcome (though I don’t believe many undergrads have bandwidth to work on outside projects, which I describe more below).

This shift towards openness was both student- and faculty-driven. The new FIELD curriculum requires that all ~900 first-year students conceive, establish, and grow a business using $5,000 in seed money from HBS. This broad shift in the first-year curriculum followed the success of Startup Tribe, HBS’s homegrown entrepreneurship club founded just two years ago. As I understand it, entrepreneurship among the HBS student body was previously an afterthought, something only a small percentage of students did. Startup Tribe helped change the entrepreneurship scene on campus, so much so that its founders recently received the Dean’s Award for their efforts.

HLS and the Harvard Law Entrepreneurship Project

Further demonstrating how Harvard’s graduate schools are now collaborating, the Harvard Law Entrepreneurship Project (HLEP) helps student startups avoid common legal pitfalls and critically assess the viability of their businesses. Each semester, after a pitching and vetting process, the Student Practice Organization pairs law student teams and an attorney advisor from Cooley, Gunderson Dettmer, or WilmerHale with ten to twelve student entrepreneur teams. All projects are also reviewed by the current General Counsel of Charles River Ventures. HLEP has worked with entrepreneurs from virtually every school at Harvard so far. Recently, HLEP’s leadership organized Hack IP, a weekend-long event dedicated to brainstorming and developing a policy about copyright that HarvardX should adopt.

i-lab Silicon Valley Trek

Another effort to raise interest in entrepreneurship as a career choice was the Innovation Lab’s trek to Silicon Valley. About 40 students, evenly split between HBS students and undergrads, Graduate School of Education, Kennedy School, and engineering graduate students, visited Silicon Valley VCs, startups, and incubators.

We heard from Michael Dearing at Harrison Metal; serial entrepreneur Mike Cassidy; Randy Komisar from Kleiner Perkins; Matthew Prince at Cloudflare; James Reinhart at thredUP; Diego Rodriguez at IDEO; and many more.

Incidentally, Cloudflare was founded on that same trip in 2009, when founders Matt Prince and Michelle Zatlyn developed the idea in the hotel bar in between trips to startups. Having that in mind as we visited Harvard alumni across the Valley was even more inspiring. From my understanding, the general consensus from students on the trip was that they were newly inspired and driven to get a career at a startup after graduating.

Here’s a short video chronicling our trip.

Recruiting

There is no shortage of startup opportunities for students, but it can be hard to sort out the good opportunities from the bad. The main recruiting mailing lists get 5-10 emails a day with startup opportunities. Here are a few excerpts of a few of the more interesting requests.

We are looking for a technical co-founder who can build and design all aspects of the website, including creating an attractive product and managing the back-end database. The programmer should know (or be willing and able to learn quickly) PHP, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and MySQL at a minimum. Familiarity with jQuery would be beneficial. The programmer should be able to essentially replicate Pinterest, or be confident that they can learn how to do so in a short period of time. Please provide any examples of previous work, if any. Our engineer will be an equity partner in what we believe will be a very profitable business and great learning opportunity. We are also open to discussing salaried compensation instead of equity. The co-founder will join a team with experiences ranging from entrepreneurship, design, consulting, and law, and will learn about the contacts and skills necessary to start a new venture.

and

I have a project which I need your assistance on. What am I offering? A partnership. I have a concept which I believe is worth pursuing. It most likely will involve php, sql, and rss. The first step would be letting me know if you are interested or not (I know some of you are very busy). The second step would be a non-disclosure agreement. I would then explain the concept, and you could tell me if you are interested in helping develop it. You would then tell me what percentage ownership in the company you would be seeking. I would then see which offer is a match between ownership and skills and select. You pick your own team. We will make it work. I look foward to hearing from you.

On the other hand, we also get a number of recruiting requests from exciting, well-funded San Francisco, New York, and Boston startups looking for students to fill internship and full-time positions.

If you’re interested in recruiting Harvard students, there are two main outlets to do so. First, contact the Office of Career Services. They’re the official middleman between employers and students, and they’re incredibly committed to increasing the number of students who go into the startup world after graduation. They can help get your job posting submitted into the Harvard job posting database, and will be able to tell you what career fairs are coming up. Second, submit your posting to [email protected]. Most CS students are subscribed to that list, run by the Harvard Computer Society, so it’s a good way to find qualified CS students.

Thoughts

In my opinion, Harvard’s startup scene is a microcosm of the broader startup environment: There’s a lot of noise, but there are many gems in the rough that will be hugely successful.

-

· finance

This post was originally published on Medium in 2013.

I’m looking to invest in a company that:

- Is a retail market leader

- Sells everything from clothes and books to appliances and electronics

- Has a loyal customer base

- Allows customers to buy “membership” in return for special perks

- Encourages customers to buy in bulk

- Has expanded into verticals unrelated to the retail focus it had when founded

- Sells generic products under its own brand name

Any recommendations? Amazon comes to mind, but today I want to argue there’s a second, better candidate:

Ready for your crazy idea of the day?

Taxes and Physical Locations

Amazon is slowly being forced to charge users sales tax in states across the country. California, Texas, and Pennsylvania residents are all being charged tax. Just this week, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick announced Amazon would begin charging a 6.25% sales tax next fall. Amazon’s reaction to these states’ actions is to open warehouses and distribution centers, seeking to reduce their already fast shipping time to hours, not days.

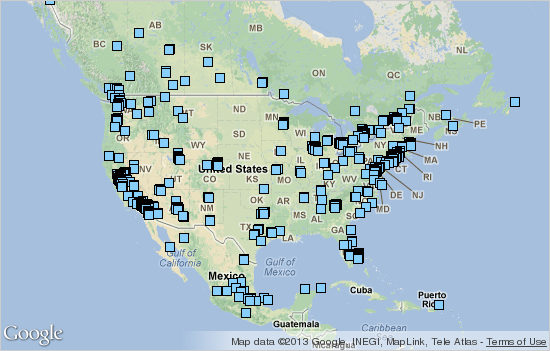

Now if you wanted to open a bunch of warehouses all across a state, located near consumers, in advance of a large-scale implementation of same-day shipping, you’d be hard pressed to find better locations than these:

That’s a map of Costco locations across the U.S. Costco has 600+ large warehouses already built, near major metropolitan areas. There’s no better way to reduce shipping time to customers than these centrally-located stores.

Warehouses

There’s a difference between buying a supermarket, or a Best Buy, or any other store, and buying Costco.

All of Costco’s stores are warehouses.

Let’s illustrate this for a second. Here’s Costco:

And here’s an Amazon warehouse:

See the similarity? I can imagine Kiva Solutions’ fulfillment robots working behind the scenes at Costco warehouses, fulfilling a user’s order while a customer picks up products in-person.

Buying in bulk

Amazon has “Subscribe and Save”. Costco’s whole premise is that you buy in bulk. The New York Times published an analysis of Costco’s prices against Amazon’s subscribe feature, and Costco came up as a cheaper option in most items, unless you take into account time to/from/at Costco. If Costco could ship to your door under the Amazon Prime umbrella, most people would just shop there.

Membership

Amazon has Prime. Costco has, well, Costco membership. Both of them use membership programs to encourage customers to buy more and buy often. Costco membership runs for $55 or $110 a year, while Amazon Prime is $79 a year (less if you’re a student).

Why not Walmart?

Assuming Amazon even wanted to buy a large physical retailer, it wouldn’t have many choices, since there aren’t many retail stores that cover the breadth of Amazon’s product selection. Walmart comes to mind, but their market cap ($230B) makes the purchase prohibitively expensive for Amazon (market cap of $130B).

Conclusion

I wrote this as a thought experiment after seeing the similarities of both Costco and Amazon on Black Friday and during the holiday shopping season. An outright merger probably won’t happen, but the two companies are definitely similar in how they operate.

-

This post was originally published on Medium in 2013.

I love New York City. It’s home, but it’s also a million cities in one. You can go from one neighborhood to another in a span of blocks, and sometimes that transition can be jarring.

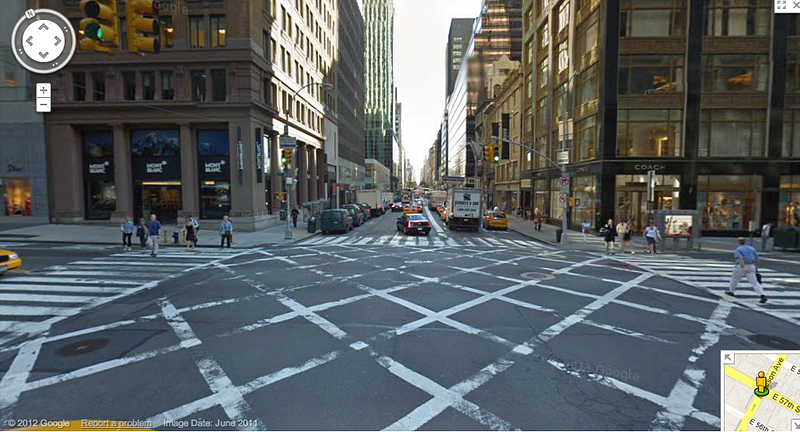

If you want a taste of those neighborhoods, just drive down Madison Avenue. Let’s start at 57th and Madison. Looking downtown, we get a glimpse of IBM’s offices.

Looking uptown, we see Mont Blanc and Coach stores across the street from each other. The next 40 blocks are similar: store after store selling luxury goods.

At 96th and Madison, the transition gradually begins. These large apartment buildings are the last ones you’ll see with penthouses for a while.

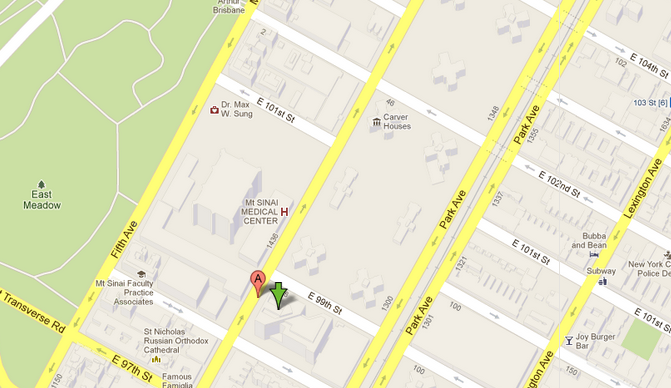

At 98th and Madison, you reach a 3 block stretch of Mount Sinai hospital complexes.

When I was a kid, there were only 2 buildings. Slowly but surely, the hospital has bought whole blocks of the surrounding area and built a complex of emergency rooms, teaching hospitals, and doctors’ offices.

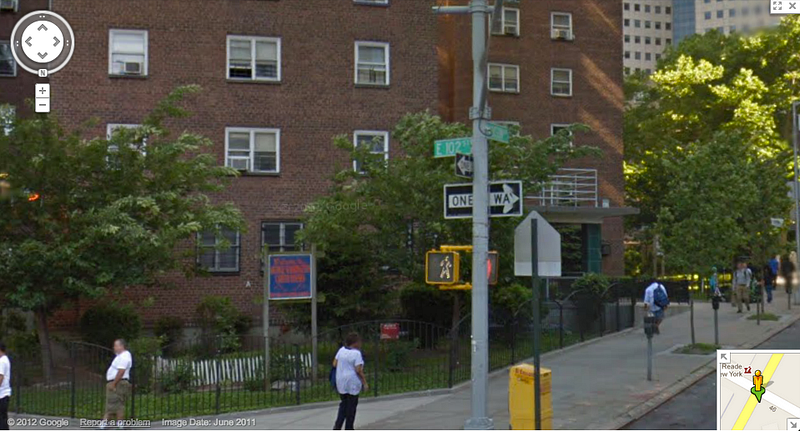

At 102nd and Madison, construction on a beautiful new building that houses classrooms for Mt. Sinai’s medical school just finished.

That new medical school sits across the street from the George Washington Carver houses, one of the first project complexes you’ll enter on the way into East Harlem.

And at 103rd and Madison, you see a 1950s-era public school across the street from another low-income housing complex. It’s the school I attended for nearly 8 years in elementary school, but more on that later.

There’s no real 100th and Madison, since 100th Street never actually intersects Madison. But it acts as a sort of “Platform 9 3/4,” dividing two very different socioeconomic classes. It’s a divide that shouldn’t exist.

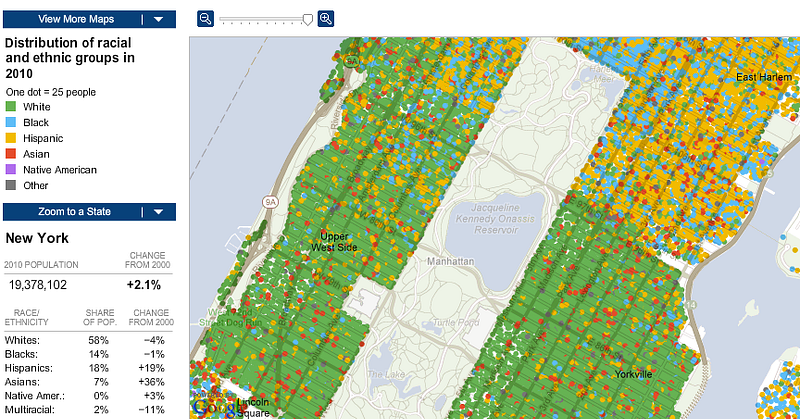

Let’s paint a more convincing picture. Here is a map of the city’s ethnic makeup based on the 2010 census, courtesy of the New York Times. Each dot represents 25 people. Green dots represent White New Yorkers, blue dots represent Black New Yorkers. Yellow dots represent Hispanics, red dots represent Asians, purple dots represent Native Americans, and grey dots represent “other”. See that line on the right side of the image where green ends and yellow begins? That’s 98th street.

How about a map of homicides from 2003-2011, also courtesy of the New York Times:

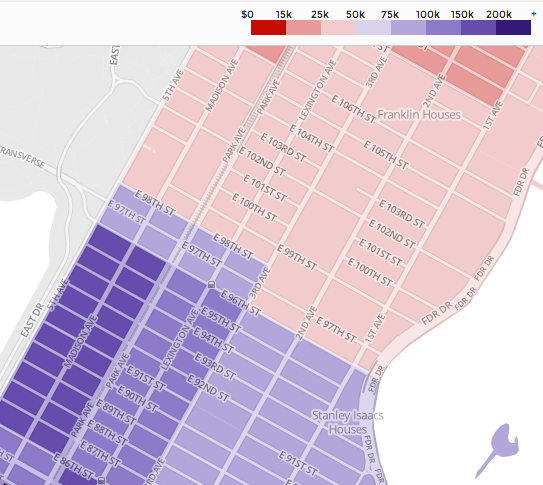

Want a clearer picture? Here’s a map of median income distribution from the 2010 census, courtesy of WNYC.

At 96th St., median income is $184,583 +/- $75,883.

At 98th St., median income is $82,750 +/- $40,958.

At mythical 100th St. and the immediate area uptown, median income is $28,196 +/- $6,021.

It’s a $150,000 decrease of income potential in 4 blocks.

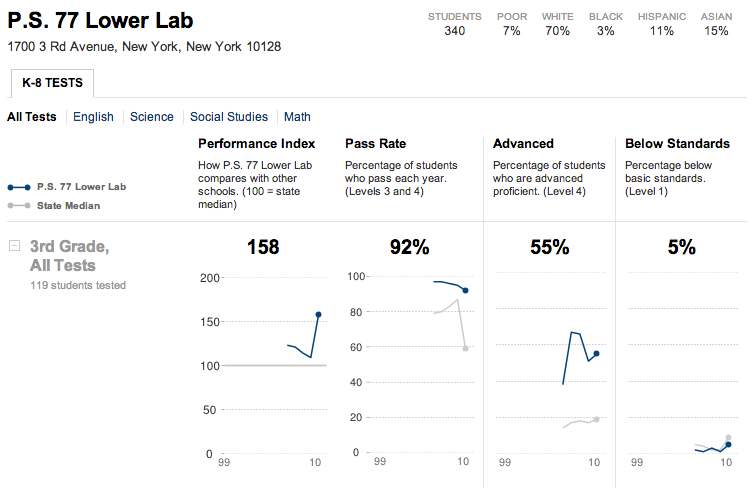

The real issue is educational opportunity. Here is a graph of student performance, courtesy of the New York Times, at P.S. 77 Lower Lab, located at 96th Street and 3rd Avenue. P.S. 77 has 340 students total (K-8). 7% are “poor,” qualifying for the federal free lunch program. 92% of 3rd graders passed their state tests, 55% were advanced proficient, and only 5% were below standard.

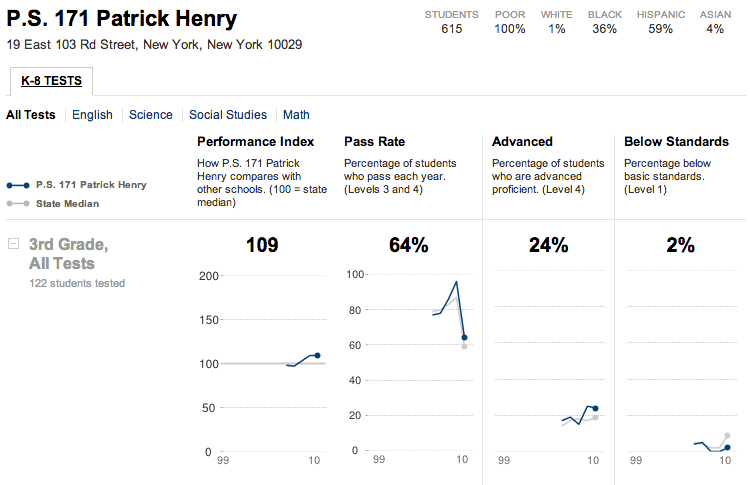

P.S. 171–the school I attended from pre-kindergarten to 6th grade–is located at 103rd and Madison. It has 615 students total (K-8), 100% of whom qualify for federal free lunch. Of third graders, 64% passed their state tests, 24% were advanced proficient, and 2% were below standard.

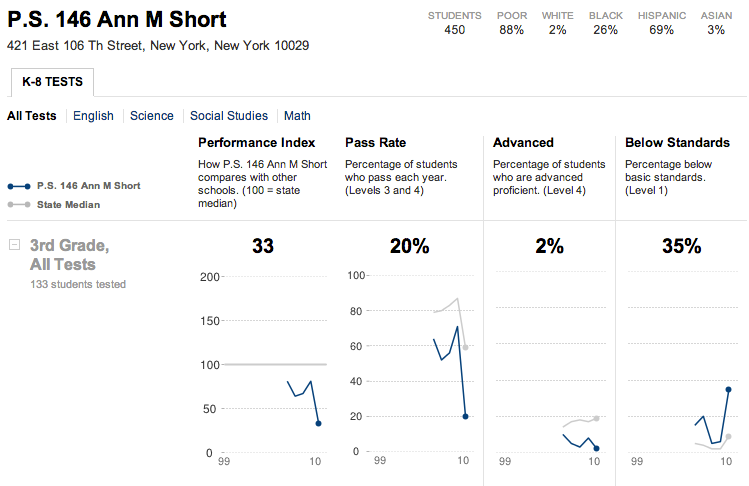

Now for P.S. 146, located at 106th Street and 1st Avenue. It has 450 students, 88% of whom qualify for federal free lunch. Yet only 20% of third graders passed their state tests, 2% were advanced proficient, and 35% were below standard.

This is how cycles of poverty start. 3 schools, 3 very different educational outcomes.

A block can make a world of difference.