-

· drafts

A running list of things that are easy to forget, relatively quick to do, and make your life easier on a daily basis.

- Review and reorder apps on homescreen

- Add keyboard shortcuts for common actions

- Add TextExpander / Alfred snippets for frequently used phrases

- Your addresses / emails in your contact card

- Share sheet ordering

- Bookmarks toolbar

- Review privacy permissions on phone and computer

- Location

- Photos

- Full disk access

- Screen recording

- Login items

- Unsubscribe from unread email newsletters

- Review and cancel SaaS subscriptions

- Notification preferences

- Alexa shortcuts

- Change major account passwords

- Two factor

- Widgets

- Chrome extensions

- Siri Shortcuts

- Phone favorites

- Pinned iMessage chats

- Default apps

- Alfred workflows

-

I purchased the Sofirn BLF SP36 ~3 years ago and it continues to be a fantastic all-around flashlight, particularly for people who need bright light outdoors at night.

It can get very bright (as in blindingly bright, so you need to be careful around others) and can illuminate objects half a mile away.

My only complaints are:

- While it charges with USB C, it needs to be via a USB A to C adapter

- The firmware it runs can get way more complex than I need, so I mainly stick with a few main modes.

Research

-

· gear

I’ve been using a Moccamaster for the past two years and love the way it makes coffee. Choosing a model was relatively hard though, since they have multiple options and models. A few friends have asked how I picked a model, so I wanted to share the 3 main decisions you’ll need to make:

1. Glass vs. stainless steel carafe

Stainless steel pros:

* Lower chance of breaking

* Will keep coffee warmer by itself longer (e.g. taking the carafe to the kitchen table)Stainless steel cons:

* Harder to clean since it’s not dishwasher safe and the mouth is narrower

* Some people are sensitive to the taste that stainless steel imparts to coffeeGlass pros

* Dishwasher safe and easy to clean by hand

* No aftertasteGlass cons

* All the glass carafe models have a hotplate to keep the coffee warm, which means there are a few more parts that could break over time

* Easier to break, though it seems quite strong2. 10 cup vs. 8 cup

For anything more than 1 person, would definitely get the 10 cup. The “cups” are European sizes (4oz), and we go through one 10 cup pot easily. Plus, you can easily make less than 10 cups if you don’t need a full carafe.

3. Manual drip stop vs auto drip stop

Manual drip stop has a switch that controls how quickly coffee leaves the brew basket into the carafe. You can close it completely to steep for longer, put it halfway to let it brew more slowly, or open fully to get a weaker cup. We keep ours on half speed all the time and that seems to work really well. Auto dripstop works as soon as you remove the carafe, which is easier but means you don’t have as much control with coffee strength etc.

Manual dripstop pros

* Can adjust how strong your coffee isManual dripstop cons

* Removing carafe midway through brew is harder — need to fully close the brew basket, use carafe, and then reopen the brew basket

* You can easily forget to reopen brew basket, which will overflow if you don’t. (We’ve gotten close to this a few times when absentmindedly making coffee in the morning).

* The mechanism is a bit finickyThere are a few other differences, but basically once you decide on those 3, there’s 1-2 models to choose from.

Ultimately I chose this model with glass carafe / 10 cup / manual drip stop — in the future, I might choose the automatic drip stop since it’s a bit easier for guests to figure out if they want to make coffee.

Other resources

- https://www.beanpoet.com/which-moccamaster-should-i-buy/

- The water pouring spout has so-so water distribution by default — new models have this new spout but you can also buy it separately for older models or there are third party options like this and this that spread the water more evenly

- Moccamaster recommends using this descaler every few weeks – I use it once a quarter with good results

-

· gear

Recently upgraded my Dyson v7 to a Dyson v11 after the battery ran out. The v11 has a larger bin, stronger suction, and swappable batteries.1

Research

- v11 absolute vs torque – only difference is soft roller attachment, which you can buy on eBay separately

- v11 torque vs animal – animal is missing the LCD screen and auto-detect mode

- Swappable batteries were introduced mid year, so not all models include them. Those bought off Dyson all have them, but if you’re buying used you’ll want to look for a red switch on the bottom of the battery indicating it can be removed easily. Other Dysons have replaceable batteries, but they require a screwdriver so you can’t do it intraday. ↩︎

-

· design

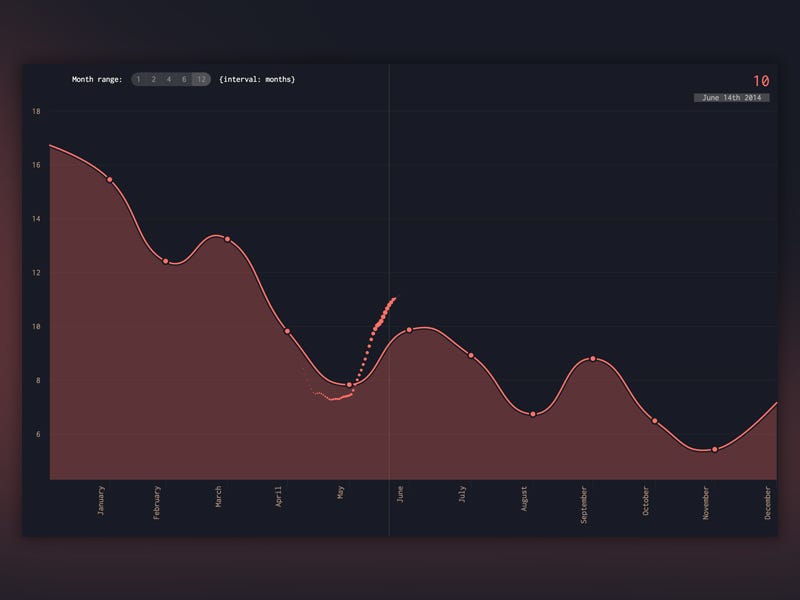

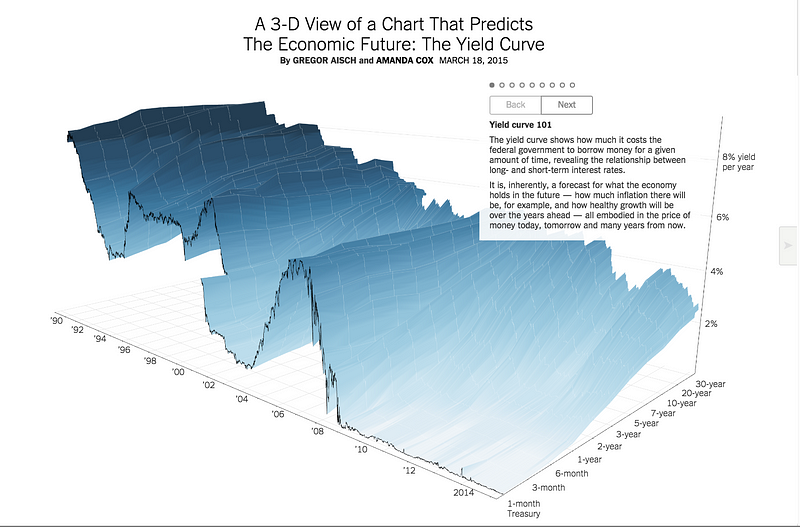

This post was originally published on Medium in 2015.

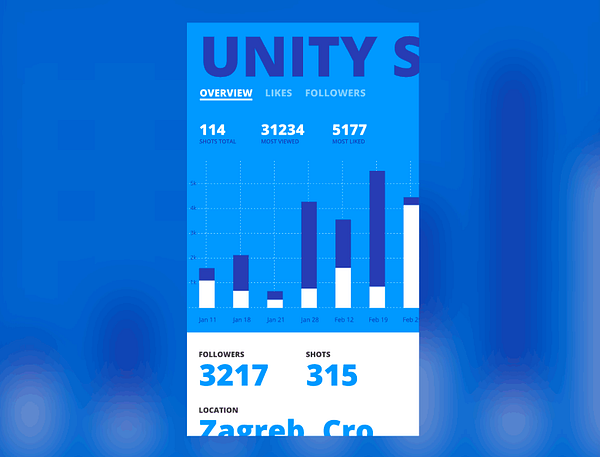

Space-saving combination of a bar chart and color-coded table. Source

Combines averaged data with a preview of the full data set as you move your cursor around. Source

Storytelling + financial data in a relatively easy to understand format due to intelligent shading, color choice, and animation. Source

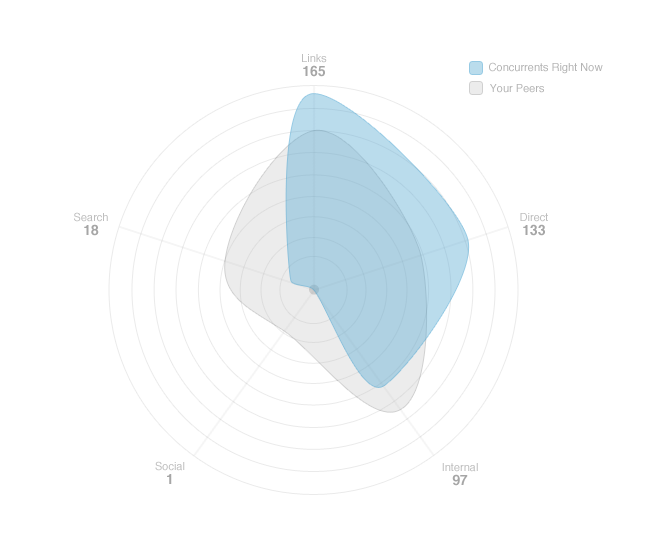

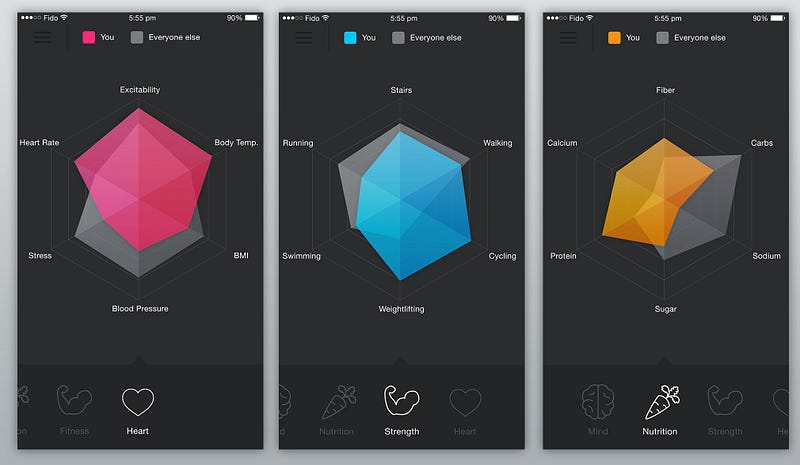

Radar chart that presents data on five axes, using transparency to make comparison easy. Source

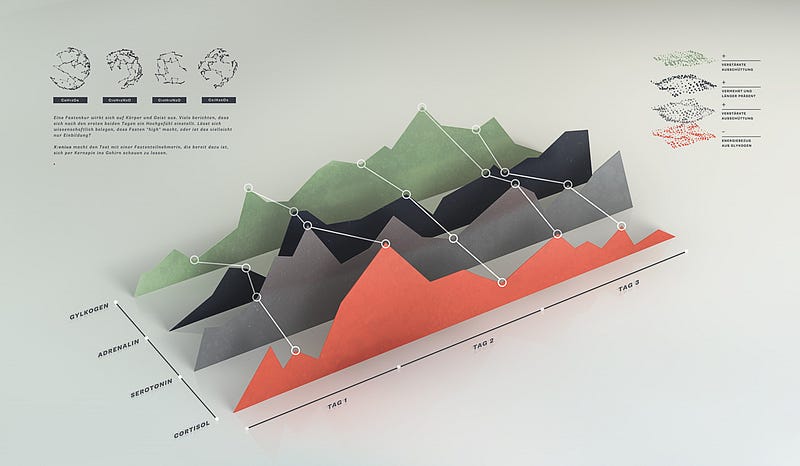

Attractive line charts that stay bearable in 3D because of overlaid elevation markers. Source

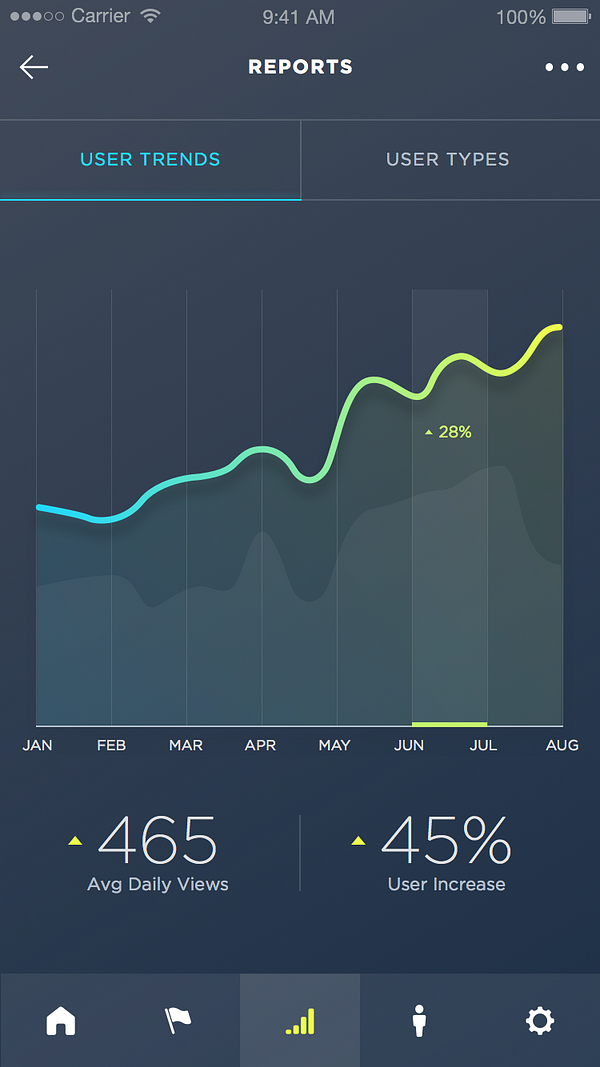

Great color choice and chart annotations. Source

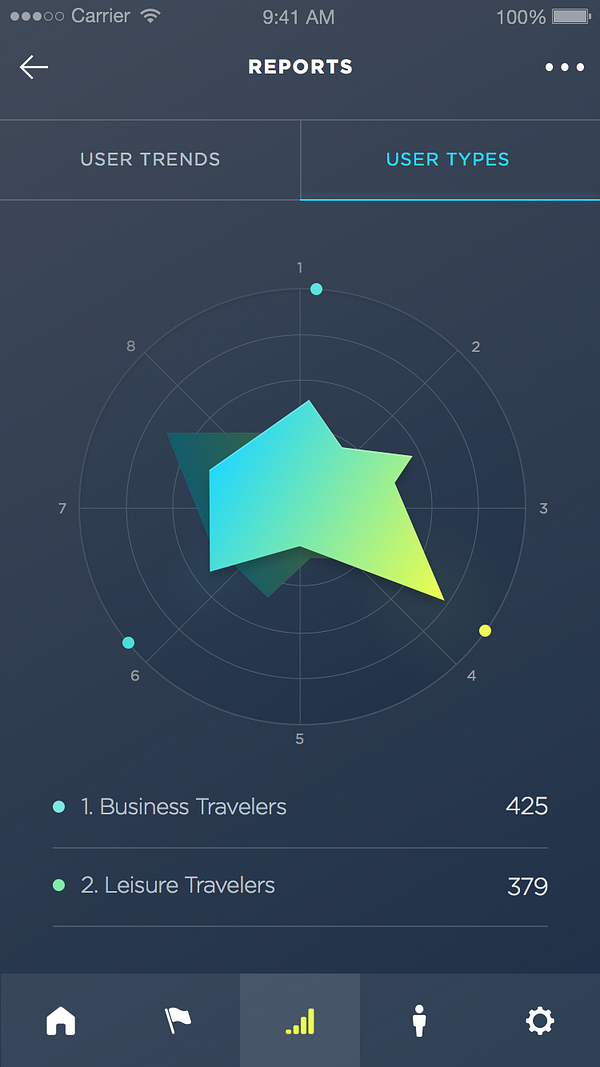

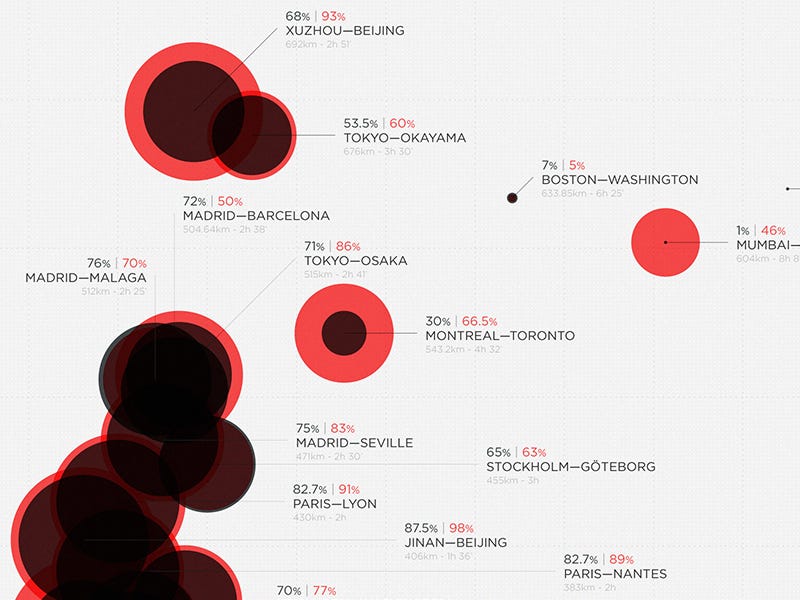

Great use of color and shapes, though hard to read at times. Source

Radar charts again used to quickly present comparisons. Source

Great use of animation to show cyclical data. Source

Seamless transitions between different chart types. Source

-

This post was originally published on Forbes and Seeking Alpha in 2015.

While only four states—Nevada, California, Florida, and Michigan—have allowed driverless cars on public roads, many experts agree that self-driving cars could be used in controlled environments like highways by 2020. And a study of 2,000 drivers found that more than 75% of Americans would consider buying a self-driving car.

So let’s take it as a given that cars will get increasingly automated over the next few decades. Are there publicly traded companies—auto makers, tech firms, manufacturers, or infrastructure providers—that are well-positioned to capitalize on this huge shift in transportation?

Disclaimer: I do not currently own shares in any of these stocks, but plan to buy some due to my research. I will update this post if and when I do buy shares in any of the below.

If one of these companies built a driverless car…

Google (NASDAQ:GOOG)

From both a hardware and software IP perspective, Google has the largest head start in this space. They’ve started building 100 adorable two-seaters and will begin testing them by early next year.

It’s unclear whether Google intends to make their own cars or license their technology. In any event, they have been granted one patent so far (“Transitioning a mixed-mode vehicle to autonomous mode”) and four more pending: Traffic Signal Mapping and Detection, Zone Driving, Diagnosis and Repair for Autonomous Vehicles, and System and Method for Predicting Behaviors of Detected Objects.

Audi (ETR:NSU)

Audi was the second company granted a license to test autonomous cars in Nevada (Google was first). Their research car, a collaboration with Stanford University, autonomously completed a 13-mile, 156-turn circuit in 27 minutes. At the 2014 Consumer Electronics Show, it debuted a vehicle that can drive without human intervention at speeds up to 40 miles per hour. Last weekend, an Audi autonomous car drove unassisted on a German racetrack, hitting 140 miles an hour at one point. They’re also working on a self-parking system that will allow drivers to exit a vehicle and let a car find a parking spot on its own. Audi executives predict Japan would be the first market to see such features in their cars, adding that “the traffic and parking situation in Japan is quite outstanding.”

Mercedes-Benz (ETR:DAI)

Mercedes already has partial-automated driving features on the Mercedes-Benz E and S-Class models. It hopes to have a fully autonomous version of its S-class sedan by 2020. At CES this year, it unveiled a radical new driverless car prototype.

It’s also committed to making autonomous trucks—it hopes to have a fully-autonomous truck on the road by 2025, and has already run tests of an autonomous truck on the German Autobahn. According to Daimler board member Dr. Wolfgang Bernhard, “the truck of the future is a Mercedes-Benz that drives itself. The Future Truck 2025 is our response to the major challenges and opportunities associated with road freight transport in the future.” In many ways, driverless trucks are likely to happen sooner than driverless cars. Vox lists out the reasons why.

…then they would need to buy from these suppliers…

FlexRay Protocol Companies: Freescale Semiconductor (NYSE:FSL) and NXP Semiconductors (NASDAQ:NXPI)

According to a new report covered by the IEEE, driverless car-compliant microcontroller and processor units will be a $500 million market by 2020, up from $69 million last year. These units will likely conform to the new FlexRay data protocol, created by a (now defunct) consortium of companies who create electronics for driverless cars. It’s 10-times faster than the current CAN messaging protocol used in cars, and is safer since it has two independent messaging channels.

Freescale Semiconductor is already a thought leader in the space, leading conferences and partnering with Formula One to investigate potential partnerships. More importantly, it’s already trusted by car manufacturers. According to Mike O’Brien, a U.S.-based VP of product planning for Hyundai, “we don’t get a beta test with our products—they have to work from the first one,” explaining the company’s cautious approach to chips in its cars.

NXP is also a leader in the chip space, having co-invested with Cisco in a startup that lets cars “see” around corners.

Mobileye (NYSE:MBLY)

Mobileye’s IPO two months ago was the best performing U.S. IPO since Twitter. Their technology senses obstructions and lanes, and can alert drivers of a collision. Their prospectus made clear they intend to be a leader in this space:

Our sophisticated software algorithms and proprietary EyeQ® system on a chip (“SoC”) combine high performance, low energy consumption and low cost, with automotive-grade standards to provide drivers with interpretations of a scene in real-time and an immediate evaluation based on the analysis. Our products use monocular camera processing that works accurately alone, or together with radar for redundancy. We expect to launch products that work with multi-focal cameras for automated driving applications with the same high performance, low energy consumption and low cost starting in 2016.

RBC Capital Markets predicts the company will “experience hyper growth through the end of the decade” with a compound annual growth rate of near 50%, adding that Mobileye is the “only real ‘pure-play’ for investors looking for ADAS and autonomous driving exposure.”

However, there are downsides to the stock. Mobileye currently trades at 190-times forward earnings, and Goldman Sachs downgraded their rating to “Neutral”. After Tesla announced that Mobileye will power the autopilot feature on its Model S cars, Mobileye stock dropped ~27%.

STMicroelectronics (NYSE:STM)

Who makes Mobileye’s chips? STMicroelectronics. They’re the leading automotive semiconductor company, and while it’s unclear what their relationship will be with Mobileye, Google, and carmakers, they have the infrastructure to manufacture chips on a level few others do. And in 2013, “revenues increased 3.2%, a better performance than the [Serviceable Addressable Market], with the main contributions coming from microcontrollers and automotive products.”

Nokia (NYSE:NOK)

After Nokia sold its mobile phone division to Microsoft for $7.5 billion earlier this year, it’s a far leaner company with a very relevant core competency: mapping.

The Nokia HERE division owns map data that originally belonged to Navteq. HERE Maps use 80,000+ data sources including cars on the ground that collect data through panoramic cameras, laser technology for 3D views, LIDAR sensors, and high-resolution cameras that capture street name signs and speed limits. That division also acquired Berkeley-based Earthmine. Nokia HERE already powers 4 out of 5 cars with in-dash navigation systems.

Nokia HERE has 90% market share for embedded automotive maps and its VP of connected driving says Nokia is building a map database specifically for driverless cars. Post-spinoff, Nokia is now a lean map company that will be a prime partner for many car companies, or an acquisition target for a company like Google looking to beef up its mapping IP.

Delphi Automotive (NYSE:DLPH)

Delphi is a spinoff of General Motors that is now one of the largest automotive part manufacturers. Although its CEO has warned driverless cars might be further off than people realize, he has also promised that the company will build parts and sensors whether cars are 10%, 80%, or 100% autonomous.

Autoliv (NYSE:ALV)

Autoliv manufactures a variety of car safety sensors, including cameras that can detect pedestrians, a night vision camera that can detect upcoming obstacles, and a smart seat belt that can restrain passengers even before a collision occurs. Their radar systems are already in higher-end cars.

…and change the economics of other verticals.

Wireless Infrastructure: American Tower (NYSE:AMT)

More vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-web communication means a greater need for wireless infrastructure. American Tower owns and operates 69,000+ wireless transmission sites in 13 countries. Their sites are well-positioned if every car on the road is communicating with each other.

Trucking: J.B. Hunt (NASDAQ:JBHT)

Labor is one of trucking’s highest expenses—the supply of qualified drivers is limited, and companies need to offer high wages, pensions, and workers’ compensation to lure candidates. J.B. Hunt has ~25% of the U.S. trucking market, 10% operating margins, and 16% expected earnings growth. However, trucking might be the last to benefit from driverless vehicles due to union opposition and varying state regulations.

Resources to Follow

- @jarden: The UX Design lead for the Google driverless car project, Jenny has presented and shared the intricacies of designing for a completely new transportation medium.

- @CarsThatThink: The IEEE’s blog on sensors and driverless cars.

- Cruise: Created by one of Twitch’s co-founders, Cruise allows you to retrofit an existing car for autonomous highway driving.

- Peloton Technology: Building connected and driverless trucks.

Conclusion

Never before has it been so clear that the transportation industry is heading in a certain direction. Some companies are better positioned to capitalize on this shift than others. But every long-term investor should look at these companies with a critical eye and imagine a world in which drivers become passengers.

-

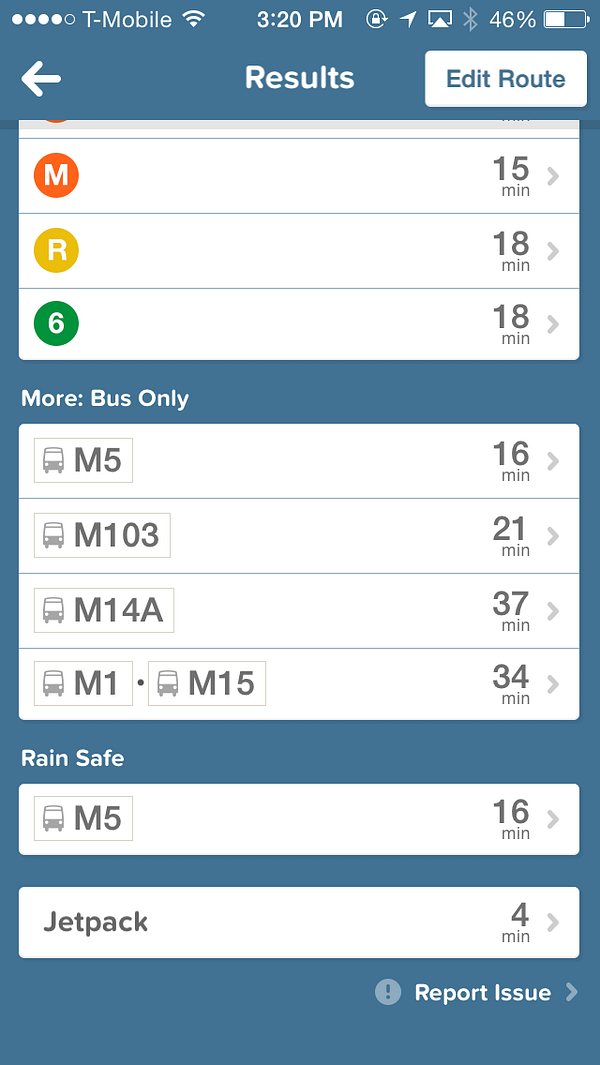

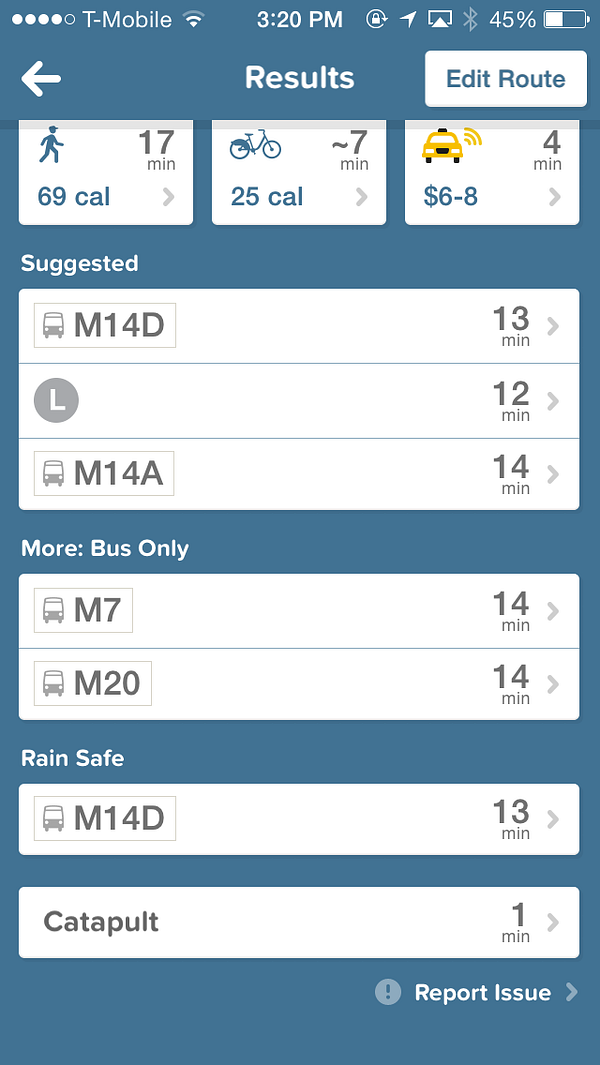

Citymapper is what happens when you actually understand user experience.

This post was originally published on Medium in 2014.

Every so often, an app comes along that just completely understands the way you think. I don’t normally write long posts about an app I’ve used. But Citymapper is so incredibly well-made that I decided to put together a list of common use cases of a maps app, and how both Google Maps and Citymapper handle them.

Scenario 1: I need to get somewhere as fast as possible.

Citymapper, 10 seconds: I can see all 4 options (public transport, walking, car/taxi, and biking) side-by-side, allowing me to compare options quickly.

Google Maps, 20 seconds: I need to click through each individual option and remember which is the fastest. Also, the flyover animation is cool but unnecessary when I’m trying to see what the fastest time is.

Scenario 2: I want to see the time needed to get from point A to point B.

Citymapper, 10 seconds: I can enter my origin and destination at the same time.

Google Maps, 30 seconds: I need to first enter my destination, then specify how I want to get there, and then change my origin from “My Location” to a different address.

Scenario 3: What are the trains near me?

Citymapper, 2 seconds: Since I know the subway system pretty well, I don’t always need full directions — I just need to know where the closest subways are so I can judge which one I should take. With one click on the train icon, I can see all the trains near me, sorted by distance. Same thing for buses.

Google Maps, 30+ seconds: There’s no way to see all nearby trains, so you have to manually look around your waypoint and click on each station. There is a public transit option in the sidenav, but it only highlights the lines on the map and you still need to click through to see which stations are closest. And at transit hubs (in this case, Union Square) it considers different subway entrances and lines as separate, so it won’t let you see aggregate information for a particular station.

Scenario 4: How long will it take me to get somewhere by Citibike?

Google Maps, can’t do it: Google Maps doesn’t have bikeshare integration, so I’m forced to switch apps and use the equally scatterbrained Citibike app to find availability.

Citymapper, 15 seconds: Not only does Citymapper find where the nearest Citibike location is and let me choose whether I want the fastest route or the quietest (read: safest) route, it also notices that the closest Citibike location to my destination has no available spaces and reroutes me to the next closest one that does. That’s magical.

Scenario 5: I just searched for directions at the office, and now I want to see those directions again.

Citymapper, 5 seconds: Previously searched destinations can be found right underneath the search bar for easy access.

Google Maps, 10 seconds — if you know where to find it: For some reason, previously searched destinations are found under your profile (the person icon next to the search bar) instead of when I search. I never noticed that until I started writing this post.

Scenario 6: I’m late to a meeting so I’m sprinting as quickly as possible down the street, looking at my phone for directions.

In any other app, shaking my phone might mean “undo last action” (e.g. Mailbox) or “submit feedback” (e.g. some beta builds of mobile apps). In a maps app, though, there’s pretty much one thing a shaking phone means — I’m running, biking, or just moving. And when I do any of that with Google Maps, this happens:

It blocks my view, it shuts off turn-by-turn directions, and is altogether a pretty terrible interaction.

Other design details

City icons

Going to a different city? Citymapper’s customized icons for each of its supported metro areas gives the app personality.

Offline subway map

If you’re in the subway, you can access a full offline zoomable subway map by clicking on an icon on the homescreen. They also have a “Save trips” option on the directions screen so you can save directions for offline use (e.g. on a subway).

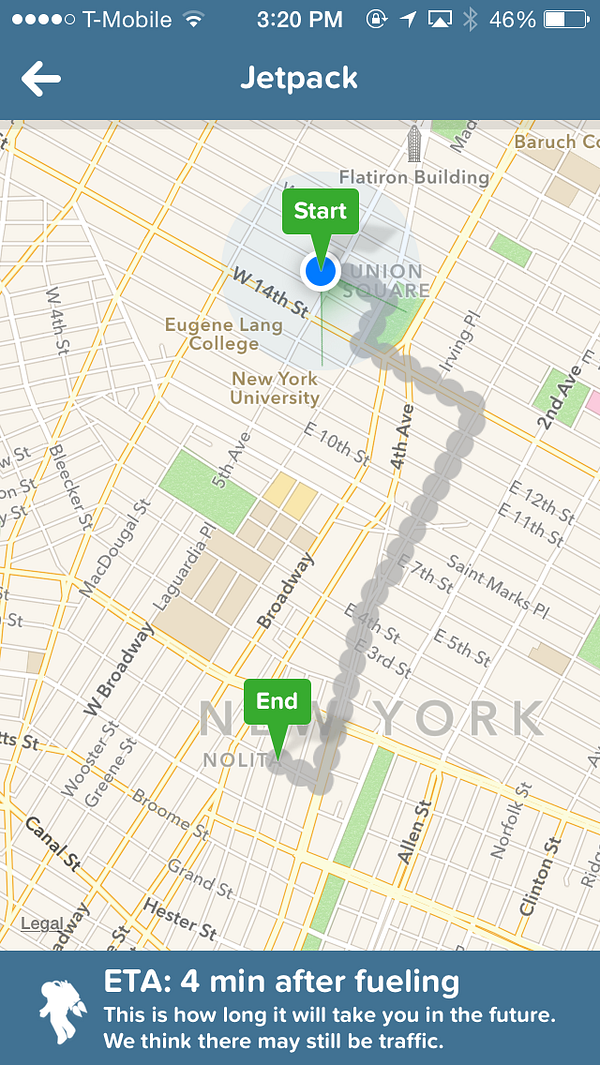

Humor

First, their release notes are legitimately funny (see Twitter examples).

And when presenting your transit options, Citymapper will occasionally throw in a funny option:

or sometimes:

But I guess I’m easily amused.

Final thoughts

Citymapper is more thoughtfully designed for urban travel. But for people who drive cars, something like Waze — with its fullscreen interface and crowdsourced realtime information — is a better choice.

And there are still features I would love to have in Citymapper. Turn-by-turn directions. Spoken directions for when I’m on a Citibike. Maybe personalized time estimates that are tailored to my walking, running, and biking speeds. But whatever Citymapper adds to the app in the coming months, I know it will be thoughtfully engineered and designed to make finding directions almost fun.

If you’re so inclined, you can download Citymapper here. (And disclaimer: I have no relation to Citymapper. Just a happy user. They didn’t even know I was writing this post.)

-

· design

This post was originally published on Medium in 2014.

Ask any Mac power user about their menubar and you’ll get a different list of 5-10 must-have applications and utilities that boost productivity. The menubar is the mission control of a user’s computer, giving them an at-a-glance view of stats and apps that are important to them. The menubar can become so crowded, in fact, that’s there’s a menubar app that collects menubar apps. So meta.

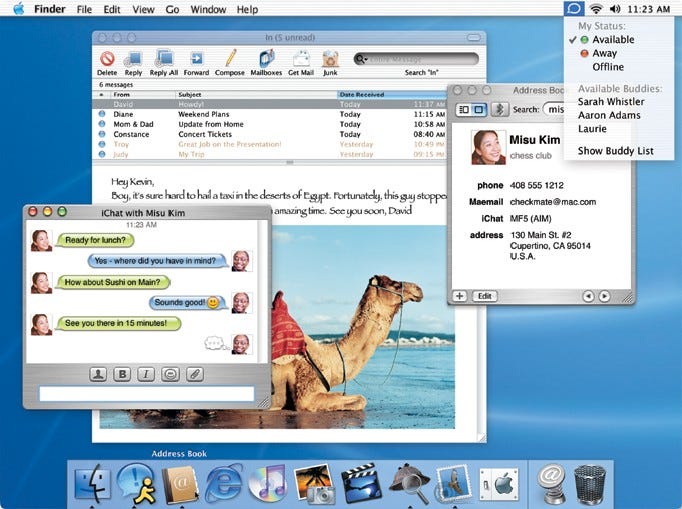

History of the Menubar App

As far as I can tell, the first menubar app appeared in the 2002 release of Mac OS X 10.2, nicknamed Jaguar. Apple had just released iChat, and part of the iChat interface was the ability to change your availability status from the menubar. But as Mac Developer Ari Weinstein has pointed out in a note, “NSStatusItem, the API developers use to create menu items, has existed since OS X 10.0 (or longer, it probably originated as part of Rhapsody in the late ’90s).”

By 2005 and the release of OS X 10.4 Tiger, other apps began to use the menubar interface to expose app status, preferences, and frequently-used features.

The menubar is a uniquely restrictive interface. Animations on the menubar icon can be distracting, but can also be a useful status indicator. Windows aren’t persistent, so you can’t count on the user keeping the window open as they multitask.

In short, menubar apps face unique design constraints. Let’s take a look at 15 apps with a menubar presence— Caffeine, Layervault, Skitch, F.lux, Cloudup, Crashplan, 1Password, Day One, Dropbox, Twitter, Cloudapp, Evernote, Droplr, Fantastical, and Mint.

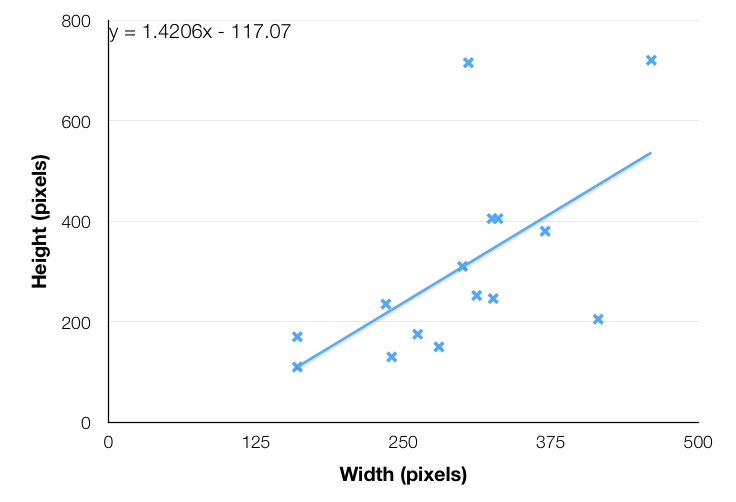

Window dimensions

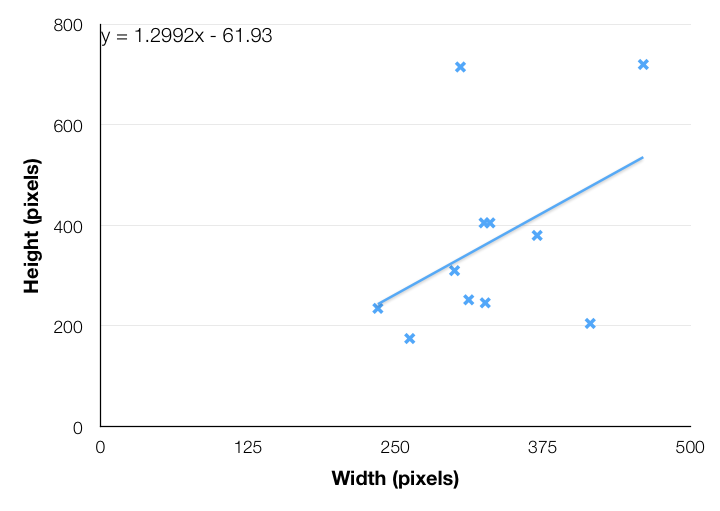

The sizes and aspect ratios of 15 top menubar apps range pretty significantly:

Width vs. Height (in Pixels) of the Apps Listed Above

This isn’t an entirely fair comparison, however, since not all the apps are stateful. Some (like Caffeine) are glorified context menus, while others (like Mint) display changing information and allow users to interact with the app. If we remove Caffeine, Skitch, Layervault, and F.lux, we get a good estimate of the ratio of width:height for full-blown menubar apps.

Width vs. Height (in Pixels) of Stateful Menubar Apps

Resource Usage

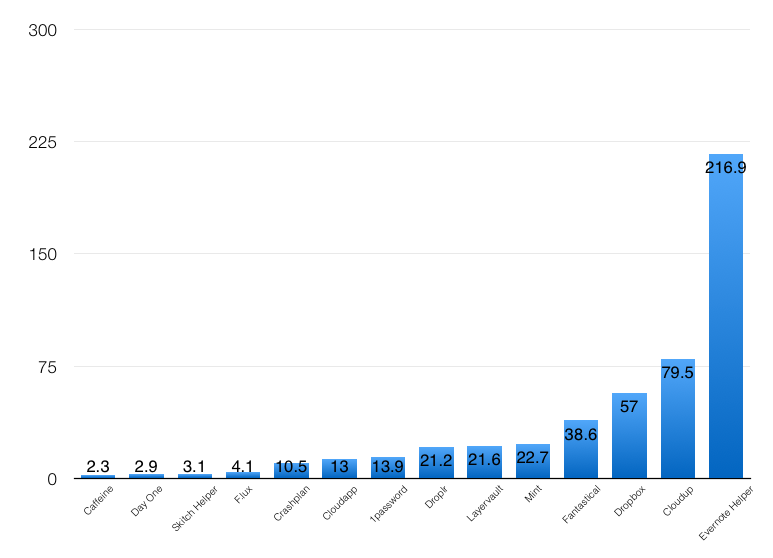

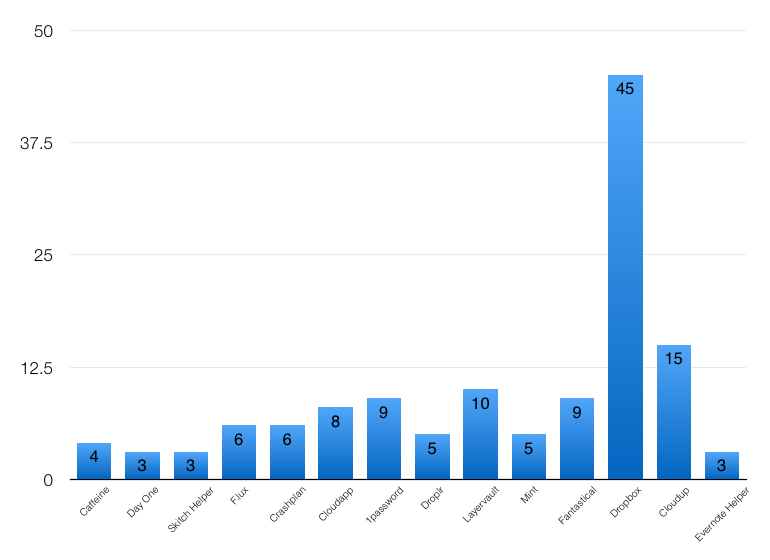

A few things about my process here — these metrics were taken on a Late 2013 Retina Macbook Pro running OS X 10.9.4 with Activity Monitor 10 minutes after a fresh restart (to deal with any usage spikes immediately after a restart). None of the apps were doing active work (e.g. Dropbox wasn’t syncing any files). I only took metrics for the “helper” process if the menubar app was an interface for a larger app (e.g. Evernote and Skitch have separate app and menubar processes). And I excluded Twitter because it doesn’t have a separate menubar process and it didn’t seem fair to include the entire app’s usage in the comparison. Obviously some of these stats will depend on your system, hardware, OS, etc.

RAM Usage (in megabytes)

Processor threads used

Most Common Colors Used in Icons

Quit with ⌘Q?

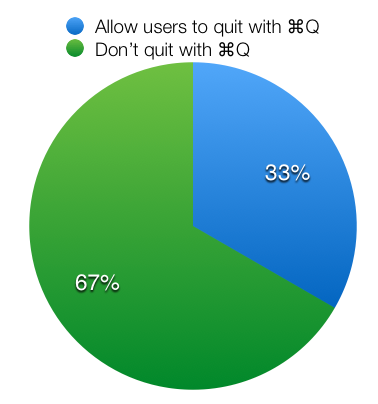

Only 5 of the 15 apps (Cloudup, Cloudapp, Droplr, Fantastical, Mint) listed allow users to quit the app by pressing ⌘+Q while the menubar app is enabled.

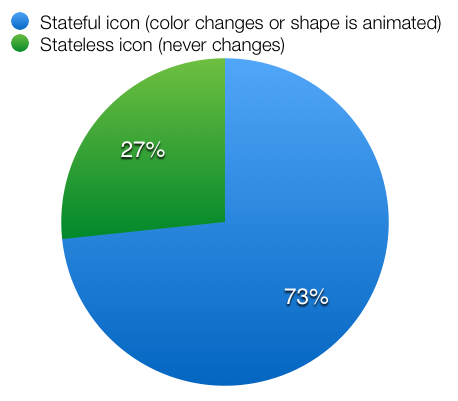

Icon interactivity

Most of the menubar apps have an icon that animates or changes color (i.e. the Dropbox icon when files are syncing). Only 4 don’t— 1Password, F.lux, Skitch, and Evernote.

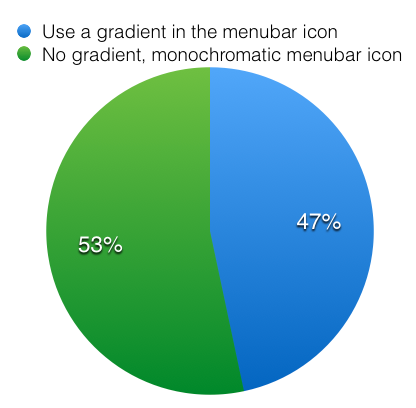

Gradient in menubar icon

There’s no consensus on whether menubar icons should be monochromatic (all black) or use a gradient.

Thanks for reading!

Like this post? You should also check out Bowery.io, an easy way to set up your development environment, visit my website, or follow me on Twitter at @zmh.

-

The art and science of creating chance

This post was originally published on Medium in 2015.

In 2014 I was lucky enough to speak at Morning Prayers, a secular Harvard tradition that has existed since its founding in 1636. Below is a copy of my remarks.

Good morning. My name is Zachary Hamed, and I am a senior in Leverett House studying computer science. I’d like to begin with a reading from Ecclesiastes:

The race is not to the swift or the battle to the strong, nor does food come to the wise or wealth to the brilliant or favor to the learned; but time and chance happen to them all.

Chance—and its sister, serendipity—are the under-appreciated forces that drive the twists and turns in life. Serendipity is defined as the “the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way.” It was first penned by Horace Walpole in a letter to Horace Mann in 1754, who said he was inspired by an old Persian fairy tale called “The Three Princes of Serendip.”

As the story goes, the King of Serendip had three sons, whom he had educated with the best tutors in the land. After several years, the king felt his sons had mastered all the knowledge of the arts and sciences, but feared they had been too sheltered and privileged in their education. He sent his sons to the desert, where they wandered for days.

Late in their trip, they met a farmer who asked if they had seen his missing camel. The princes asked the farmer if his camel was blind in one eye, had a gap in its teeth, and was injured in one leg. When the farmer heard this, he accused the princes of stealing his camel and took them to the king.

When the king asked how his sons knew such intimate details of a stranger’s camel, they explained that their days of wandering had led them to notice small details in the environment. An animal had eaten the tougher and browner grass on the left side of the road, leading them to believe the animal was blind in one eye. There were lumps of chewed grass along the road that were the size of a camel’s tooth. And there were only 3 camel footprints on the road with the fourth being dragged, leading them to believe the camel was disabled in one leg. As soon as they finished, a traveller entered and reported he had found a lost camel in the desert. The princes were rewarded handsomely and their intuition trusted for years to come.

The story hits close to home because Cambridge resembles Serendip all too often. It is easy for us to be so ensconced in our research, our work, our meetings and our routine that we don’t make time for productive and creative wandering.

In the 1950s, a pair of medical researchers—one at NYU and one at Cornell—accidentally injected rabbits with a certain enzyme and noticed that the rabbits’ ears folded over. Neither had the time or funding to pursue the anomaly, so they buried it away in their lab notebooks. Several years later, only one of the professors decided to review his research notes when he realized the flopping ears were actually more important than his initial research was. His work led to a Nobel Prize, and a subsequent sociology paper on the topic coined the terms serendipity gained (for example, reviewing your notes and deciding to pursue a question further) and serendipity lost—making the same discovery but never following up.

In short, serendipity enters our lives several times a day. We can gain it or lose it. But the best part is—we can engineer it. MIT Professor Ethan Zuckerman covers this phenomenon of creating luck. “Engineering serendipity,” he says, “is this idea that we can help people come across unexpected but helpful connections at a better than random rate. And in some ways it’s based on trying to reassess this notion of serendipitous as lucky — to think of serendipitous as smart.”

Harvard engineers serendipity at every point it can. You’re placed with a random group of your classmates when you enter as a freshman. Even when you’re allowed to choose your roommates in sophomore year, you’re placed randomly into houses and a lottery randomly places you into rooms. The lectures in your general education class could help you on a completely unrelated assignment in a different class. And have you noticed how many walking paths there are outside this very church? Walking through Harvard Yard is a case study in serendipity—it’s almost impossible to avoid seeing someone you know.

We meet best friends at events in Ticknor Lounge, significant others in early morning sections in Sever, mentors over lunch in Leverett dining hall, and overhear job opportunities in Lamont Cafe. Every minute on Harvard’s campus is a chance encounter waiting to happen.

Harvard’s secret is it takes a diverse group of people and squeezes them into a small, confined space. But the real world is a big place. And the scariest part is that serendipity will no longer be engineered for us. In fact, New York City, where I’ve been living for the past 4 months, seems to be engineered against serendipity. Have you ever tried meeting someone new on a New York City subway train? In a city of 8 million people, how do you find your new best friend? Your new job opportunity?

As always, Ralph Waldo Emerson provides the answer. “Shallow men,” he says, “believe in luck or in circumstance. Strong men believe in cause and effect.” It is up to us to engineer serendipity once we leave Harvard’s gates. So talk to the person behind you in line at the coffee shop. Knock on your neighbor’s door in the otherwise anonymous apartment building you live in. Ask your friends to introduce you to someone new and go to lunch with them.

Be open to the unexpected today. Relish the uncertain. And embrace serendipity.